John Walk

What is Fusion?

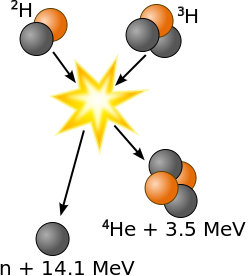

Fusion is the nuclear reaction driving the core of stars. Whereas fission (the reaction driving current nuclear power plants) operates by splitting heavy nuclei (e.g., Uranium or Plutonium) apart, fusion releases energy by smashing light nuclei (mainly isotopes of Hydrogen) together. Like fission nuclear power, fusion releases an enormous amount of energy from a very small amount of fuel - 339 million MJ/kg of Deuterium-Tritium fusion fuel, compared to 80 million MJ/kg for Uranium fission fuel or a paltry 29 MJ/kg of burned coal. Moreover, nuclear (fission or fusion) power releases no pollution or carbon dioxide, and can run independently from the climatic or geographic considerations limiting other “green” energy sources (wind, solar, geothermal, hydroelectric). Fusion power has a number of further advantages over fission generation as well:

- rather than difficult-to-mine heavy metals, fusion fuel is simply scraped from seawater - and is even more plentiful than Uranium fuel reserves

- due to the nature of fusion power plant operation, it is physically impossible for the plant to “melt down” - fusion power could improve the safety of nuclear power (though on a per-energy-produced basis, fission power already boasts an impressive safety record compared to other energy production methods)

- While fission power plants produce nuclear waste that remains radioactive for millenia (and is quite toxic and corrosive in addition to its radioactivity), necessitating essentially-indefinite secure storage, the waste product from fusion is small amounts of inert, stable helium gas, producing only small amounts of low-level nuclear waste from irradiated spent structural components

So why aren’t we doing this already?

Simply put, fusion is really hard due to the nature of how the reaction is triggered. In a fission power plant, the reaction is initiated by a free neutron striking a fuel nucleus - since the neutron is neutrally-charged (thus the name), it feels no force from the electrons and protons in the surrounding fuel atoms, passing through the fuel more-or-less freely until it strikes a nucleus, triggering the reaction (which in turn releases more neutrons, allowing a self-sustaining chain reaction). This means that the fission fuel can be in solid rods kept in a reactor vessel that reaches no more than a few hundred degrees in temperature - a reasonably well-understood engineering problem.

Fusion, on the other hand, requires getting two fuel nuclei close enough together to “stick” (where “close enough” means distances comparable to the nuclear size itself, roughly \(10^{-15}\) m) - since these are made up of charged particles, we must overcome electrostatic repulsion from like charges. If the fuel is a neutral gas, the electron clouds of the atoms repel each other far before the nuclei get close enough to fuse (the electron clouds are rougly \(10^{-10}\) m, 10,000 times larger in radius than the nucleus). We must get the electrons out of the way. This means heating the fuel gas until it becomes a plasma, an ionized gas - rather than the fuel consisting of neutral atoms with electrons bound to nuclei, the plasma is a hot soup of free ions and electrons, bouncing off each other, but too hot and energetic to stick and recombine into an atom. This lets the nuclei to collide directly, allowing fusion reactions to occur.

Why are fusion plasmas hard to work with?

The plasma is already very hot - Hydrogen ionizes at around 160,000 degrees Celsius. But this is (a) not hard to work with (fluorescent light bulbs actually contain a very low-density plasma at around this temperature) and (b) not good enough to get fusion. Even without the electrons in the way, we’re fighting against electrostatic repulsion - the like-charged nuclei repel each other before getting close enough to fuse. Fusion reactions require the nuclei to collide with enough energy to overcome the repulsion - this means the fusion plasma must be extremely hot, to the tune of hundreds of millions of degrees C.

This raises a crucial problem - how do we hold something this hot? With a fission plant, the reactor core is a few hundred degrees, and can be held with a metal reactor vessel. In a fusion plant, there is no material in existence that can hold the hot, fusing core of the plasma. In nature, the fusing core of a star is held together by its own immense gravity, and insulated by the surrounding vacuum of space (on earth, we have been able to initiate a brief, rapid fusion nuclear reaction in the atmosphere without insulation - this is called a thermonuclear warhead). We have to be more clever to hold a steady fusion reaction for a power plant - putting the “sun in a bottle”.

Magnetic confinement

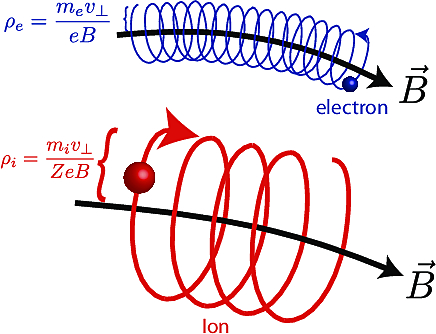

Since the plasma is made up of free, charge particles (electrons and ions), it responds strongly to electric and magnetic fields, following the Lorentz Force

\[F = q(E + v \times B)\]for electric charge \(q\), velocity \(v\), and electric and magnetic fields \(E\) and \(B\) respectively. In particular, we care about the magnetic field force - a charged particle in a magnetic field feels a force proportional to its velocity and the magnetic field strength, and oriented perpendicular to both. This leads to a phenomenon called gyro motion, in which the particle moves in a helical path around a line of constant magnetic field, with the radius of the spiral set by the particle’s momentum (leading to a looser spiral), and the charge and magnetic field strength (which tightens the spiral):

By using strong magnetic fields, we can hold the plasma such that this gyro radius is much smaller than the extent of the plasma (at fusion conditions and typical field, the gyroradius is ~10 microns for electrons and ~1mm for ions), such that the core of the plasma can be held away from contact with any of the physical walls of the machine - a “magnetic bottle”.

There is one issue: what happens at the ends of the line? The charged particle feels no force parallel to the magnetic field, so there is nothing stopping the plasma from freely streaming along the magnetic field. To hold the plasma, we twist the magnetic field into a ring - holding the plasma in a donut shape (a torus) in which charge particles can stream around the ring without contacting the walls of the device, allowing us to confine a plasmas despite the extreme temperature.

Tokamaks

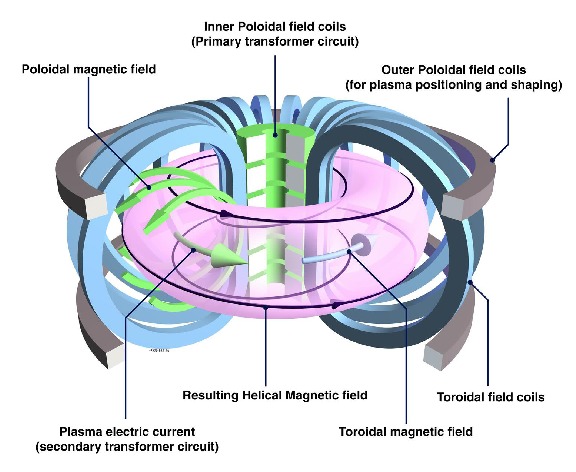

The most successful design for magnetic confinement is the tokamak, from a Russian acronym for “toroidal chamber with magnetic coils.” Tokamaks solve a fundamental problem with magnetic confinement - the need for a “twist” (termed the rotational transform) to the magnetic field to allow the plasma to remain stable and steady within the toroidal chamber.

Tokamaks achieve this twist by generating the magnetic field in two directions. The main field running the long circuit around the torus (the toroidal field) is generated by external electromagnetic coils. The twist to the field (equivalently, a second perpendicular field wrapping the short way around the donut, the poloidal field) is generated by a strong (> 1 million Ampere) electric current run through the plasma itself. This eliminates the need for the complex “kinked” coils found in stellarators, the main competing design for magnetic confinement, greatly simplifying machine engineering.

Although tokamaks have consistently shown the best performance at a given size scale in fusion experiments, there are still a number of engineering challenges for fusion reactor development - designing the materials of the reactor inner wall, efficiently heating the plasma to fusion conditions, driving the necessary plasma current in steady state, etc.

Why isn’t this a power plant yet?

The biggest challenge of all, though, is simply making the tokamak efficient enough to be economical. Even at fusion conditions, the fuel nuclei are much more likely to bounce off of each other (a Coulomb collision) rather than fuse. We have to maximize the probability that a given collision will result in fusion, which means having more energy in the collision. On top of this, we need collisions between nuclei to happen often enough that that fraction resulting in fusion adds up to a meaningful total reaction rate. At a macro scale, this simply means the plasma must be hot enough and dense enough (equivalently, at sufficient pressure) for the desired fusion reaction rate.

On top of this, the tokamak must have sufficient energy confinement, a measure of how well the plasma retains its own heat (tyically represented by a characteristic timescale for heat loss, denoted the energy confinement time \(\tau_E\)). In a reactor, some of the heat from fusion reactions must go into reheating the plasma fuel, sustaining it at sufficient temperatures to continue fusing. If this does not produce enough heat, external heating power must be applied to the plasma - on present experiments, we require more power into the plasma than we get out of it (though the largest experiments have come tantalizingly close to break-even on energy production). The simplest way to increase energy confinement is simply to build the tokamak bigger - we could build a working power plant using only 1980’s-vintage tech and physics, but it would be so large as to not be economical (the cost of electricity from a tokamak is basically the construction cost of the reactor amortized over its lifetime, and machine size determines cost). We need to build smarter, rather than brute-forcing the problem with machine size - with a better understanding of plasma physics, we can improve the confinement of smaller tokamaks for a more economical fusion reactor.

Up next: the pedestal