John Walk

Data Processing with Dask

John Walk

This was originally published on the Pluralsight Tech Blog and on the Pluralsight DS/ML Medium.

In modern data science and machine learning, it’s remarkably easy to reach a point where our typical Python tools – packages like numpy, pandas, or scikit-learn – don’t really scale suitably with our data in terms of processing time or memory usage.

This is a natural point to move to a distributed computing tool (classically, something like Apache Spark) but this can mean retooling our workflow for an entirely new system, navigating between our familiar Python ecosystem and a distinct JVM world, and greatly complicating our development workflow.

The Dask library joins the power of distributed computing with the flexibility of Python development for data science, with seamless integration to common Python data tools.

In this post, we’ll build a simple data pipeline for analytics and machine learning, working with text data in Dask.

what is distributed computing?

Consider the following scenario: you have a dataset, perhaps a collection of text files, that is too large to fit into memory on your machine.

That’s ok – we can just use Python’s file streaming and other generator tooling to iterate through our dataset without loading all of it into memory!

But… then we’re up against speed limitations, as even with all the memory cleverness we can muster the job is still running in a single thread.

Thanks to a safety feature called the Global Interpreter Lock in Python (more properly, CPython, which most people are using), writing parallel code in Python can be a little tricky.

There are several good solutions though, either by using lower-level tools outside the GIL (like numpy doing multithreaded heavy lifting in compiled non-Python code) or using multiple threads/processes from within Python code with packages like joblib or multiprocessing.

But trying to speed up your code with parallelization can be difficult to get right, and can result (even when done properly) in less readable code that requires you to completely rearchitect your process… and you’re still limited by the resources on your machine!

For truly large-scale problems like this, distributed computing can be a powerful solution. In a distributed system, rather than merely trying to work in multiple processes or threads on a single machine, work is farmed out to multiple independent worker machines, each of which is handling chunks of the dataset in its own memory and/or disk space and on its own processors. Rather than sharing memory and disk space (as properly multithreaded code would), these worker nodes only communicate with each other or a central scheduler via relatively simple messaging. In exchange for the design complexity of setting up that centralized scheduler and keeping workers fairly separate from each other (as moving data in bulk between workers is a potentially very expensive operation), distributed compute systems can let you scale code on very large datasets to run in parallel on any number of workers.

dask for distributed computing

Frequently, moving to distributed compute would require using a tool like Apache Spark. While powerful, Spark can be tricky to work with, it’s difficult to prototype with locally, requires dealing with code running in the JVM (which can by a significant mental-model switch from the typical Python code found in the DS/ML ecosystem), and is limited in its capability to handle certain tasks like first-class machine learning or large multi-dimensional vector operations. Dask aims to upend that, as a native Python tool designed from the ground up to integrate with (and in some cases, be essentially a drop-in replacement for) typical Python data tools.

Under the hood, Dask is a distributed task scheduler, rather than a data tool per se – that is, all the Dask scheduler cares about is orchestrating Delayed objects (essentially asynchronous promises wrapping arbitrary Python code) with their dependencies into an execution graph.

Compared to Spark’s fairly constrained high-level primitives (effectively, an extension of the MapReduce paradigm), this means Dask can orchestrate highly sophisticated tasks, enabling remarkable uses like multi-GPU scheduling in RAPIDS.

For our purposes, though, we don’t really need to worry about these low-level internals – Dask provides us several collections for wrapping low-level tasks into high-level workflows:

dask.bag: an unordered set, effectively a distributed replacement for Python iterators, read from text/binary files or from arbitraryDelayedsequencesdask.array: Distributed arrays with anumpy-like interface, great for scaling large matrix operationsdask.dataframe: Distributedpandas-like dataframes, for efficient handling of tabular, organized datadask_ml: distributed wrappers aroundscikit-learn-like machine-learning tools

Since it’s Python-native, starting with Dask is as simple as pip or conda installing in your environment of choice (or using one of their docker images), and it’ll run fine even on a single laptop (though the same code can, with minimal changes, be scaled up to the thousand-worker cluster use case!).

Let’s dive in!

getting started

For this example, we’ll use the archive.org open-sourced data dump of Stack Exchange data.

We’ll be pulling one of the Posts datasets, which is itself a fairly straightforward XML file, but one that can be (in the case of larger communities, like Stack Overflow) too large to fit in memory or process quickly on a single machine.

We’ll be able to do all our processing in Dask, with one simple hack to set things up – since we know the file is structured with an XML header and footer, we can go ahead and strip these from the command line:

$ sed -i '' '1,2d;$d' Posts.xml

after which every line of the text file is an independent XML row object, so we can easily shard it out across multiple workers.

We can set up our initial data read:

>>> client = dask.distributed.Client() # uses local distributed scheduler

>>> posts = dask.bag.read_text("Posts.xml", blocksize=1e8)

Once we’ve declared the Client, any operations in the same session will default to using it for computation.

By calling it without any arguments, Dask automatically starts a local cluster to run the work against.

This is one of my favorite things about Dask – compared to the lift involved in getting Spark set up for local development, I’ve found the ease of use for Dask tooling to be one of its biggest strengths.

We then simply need to read the text file (or files) into a Dask bag (“bag” here in the mathematical sense, namely an unordered set with duplicates). In practice, we really only need to think about bags as something like a distributed iterable – we can map functions onto each element, filter through them, and fold them together in a MapReduce sense. This is a great starting point for a lot of datasets where we can’t initially make many guarantees about the structure of the data.

>>> posts

dask.bag<bag-from-delayed, npartitions=1>

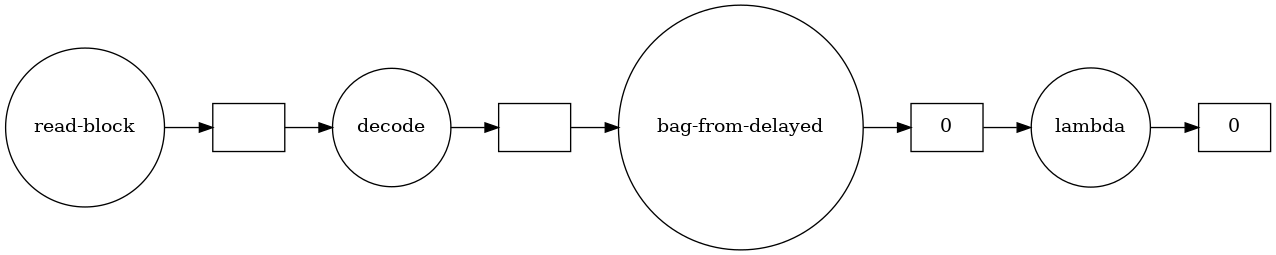

If we inspect the posts object, we’ll see a somewhat opaque reference to a dask.Delayed object instead of an actual representation of our data.

This is because the Dask scheduler is lazily building up an execution graph as we declare operations, so the object as it stands now is just a representation of the steps Dask is planning (in this case, creating a bag from a delayed file read, with a single partition since we’re working with a small demo file).

The graph won’t actually compute anything until we explicitly tell it to, allowing the scheduler to optimize its operation under the hood.

If we want to inspect our data, we can pull samples out:

>>> posts.take(1)

(' <row Id="5" PostTypeId="1" ... />\r\n',) # truncating the rest of the XML here

Dask will lazily compute just enough data to produce the representation we request, so we get a single XML row object from the file.

Naturally, we’ll start wanting to apply functions to the elements of our bag to bring order to our data, and the map() method is bread and butter for this.

Let’s get our data out of XML into a Python dictionary using the standard library’s xml.etree.ElementTree:

>>> posts = posts.map(lambda row: ElementTree.fromstring(row).attrib)

>>> posts.take(1)

({'Id': '5',

'PostTypeId': '1',

'CreationDate': '2014-05-13T23:58:30.457',

'Score': '9',

'ViewCount': '671',

'Body': '<p>I\'ve always been interested in machine learning, but I can\'t figure out one thing about starting out with a simple "Hello World" example - how can I avoid hard-coding behavior?</p>\n\n<p>For example, if I wanted to "teach" a bot how to avoid randomly placed obstacles, I couldn\'t just use relative motion, because the obstacles move around, but I don\'t want to hard code, say, distance, because that ruins the whole point of machine learning.</p>\n\n<p>Obviously, randomly generating code would be impractical, so how could I do this?</p>\n',

'OwnerUserId': '5',

'LastActivityDate': '2014-05-14T00:36:31.077',

'Title': 'How can I do simple machine learning without hard-coding behavior?',

'Tags': '<machine-learning>',

'AnswerCount': '1',

'CommentCount': '1',

'FavoriteCount': '1',

'ClosedDate': '2014-05-14T14:40:25.950'},)

Recall that Dask is just lazily building a compute graph here.

Each time we rebind the posts variable, we’re just moving that reference to the head of the graph.

We can actually see what the graph looks like with a built-in visualizer (using graphviz under the hood):

>>> posts.visualize(rankdir="LR")

Much like map, we can also filter elements of the bag from here – let’s keep only the top-level posts rather than the replies, indicated by a PostTypeId of 1:

>>> posts = posts.filter(lambda row: row["PostTypeId"] == "1")

Dask bags also support aggregation via their fold and foldby methods, which support a MapReduce-like paradigm.

However, I tend to find myself doing such operations in dataframes instead.

Fortunately, it’s easy to create dataframes once we have some semblance of structure to our data.

Now that we know the fields we care about are present, let’s go ahead and create one:

>>> metadata = {

... "Id": int,

... "CreationDate": "datetime64[ns]",

... "Body": str,

... "Tags": str

... }

>>> posts = posts.to_dataframe(meta=metadata)

Dask can try to infer datatypes, but that could lead to potentially expensive computation or errors (particularly around null-handling).

I’ve generally found it useful to go ahead and be explicit about types, especially since that gives us an immediate opportunity to filter to selected columns and apply initial data type casting.

Here we simply need to supply Python types for Dask to generate a schema.

(We can also use more esoteric types – for example, datetime64 is a numpy datatype.)

dataframe operations

Once we’ve reasonably structured our data and converted it into a tabular dask.dataframe object from our dask.bag, we find ourselves in familiar territory for data science tooling:

>>> posts.head()

Id CreationDate Body Tags

0 5 2014-05-13 23:58:30.457 <p>I've always been interested in machine lear... <machine-learning>

1 7 2014-05-14 00:11:06.457 <p>As a researcher and instructor, I'm looking... <education><open-source>

2 14 2014-05-14 01:25:59.677 <p>I am sure data science as will be discussed... <data-mining><definitions>

3 15 2014-05-14 01:41:23.110 <p>In which situations would one system be pre... <databases>

4 16 2014-05-14 01:57:56.880 <p>I use <a href="http://www.csie.ntu.edu.tw/~... <machine-learning><bigdata><libsvm>

This looks just like a normal pandas dataframe – in fact, each partition of a Dask dataframe is itself a pandas dataframe!

Our typical dataframe operations are generally supported, like renaming or accessing rows/columns by index:

>>> snakecase_regex = re.compile(r"(?<!^)(?=[A-Z])")

>>> posts.columns = [re.sub(snakecase_regex, "_", c).lower() for c in posts.columns]

We can use our typical columnar operations from pandas as well.

Numerical manipulation works as expected (since the underlying dask.array mirrors numpy operations), or we can leverage the pandas.str and pandas.dt submodules for working with string and date data.

(As an aside, underutilizing these lesser-known tools is a common mistake I’ve seen with new data scientists – often they’ll apply a string function across a column rather than using pandas builtins, which are often significantly faster).

For example, we can split the XML string of our tags out into an array, and do some simple text cleaning on the body:

>>> tag_regex = re.compile(r"(?<=<)\S*?(?=>)")

>>> posts.tags = posts.tags.str.findall(tag_regex)

>>> posts.body = posts.body.map(lambda body: BeautifulSoup(body).get_text(), meta=("body", str))

>>> posts.head()

id creation_date body tags

0 5 2014-05-13 23:58:30.457 I've always been interested in machine learnin... [machine-learning]

1 7 2014-05-14 00:11:06.457 As a researcher and instructor, I'm looking fo... [education, open-source]

2 14 2014-05-14 01:25:59.677 I am sure data science as will be discussed in... [data-mining, definitions]

3 15 2014-05-14 01:41:23.110 In which situations would one system be prefer... [databases]

4 16 2014-05-14 01:57:56.880 I use Libsvm to train data and predict classif... [machine-learning, bigdata, libsvm]

Data filtering (as you might expect) also looks like a typical pandas operation.

For example, to keep only posts tagged with python,

>>> python_posts = posts[posts.tags.map(lambda tags: "python" in tags)]

Note that, when filtering on columns that are likely to be ordered (like a datestamp), we could potentially end up removing most or all of some partitions and leave others untouched.

After operations like that, it may be worthwhile to repartition the dask.dataframe to better distribute data across its workers.

Dask will generally do this intelligently (partitioning by index as best it can), so we really just need to have a sense of how many partitions we need after filtering (alternately, how much of our data we expect to remove).

analytics & machine learning

Now that we’ve got our data in a clean representation, we can extract some useful knowledge from it.

For example, let’s look at the most common tags co-occurring with the python tag:

>>> python_posts = python_posts.explode("tags") # replicates rows, one per value in `tags`

>>> python_posts = python_posts[python_posts.tags != 'python']

>>> tag_counts = python_posts.tags.value_counts()

Inspecting this, we see we’re still in distributed land: tag_counts is bound to a Dask series (analogous to a pandas object) with all the underlying computation rolled into it.

However, we’re now at a point where the aggregated result would realistically fit in memory, so we can materialize it by simply triggering the computation:

>>> tag_counts = tag_counts.compute() # returns a pandas series

>>> tag_counts.head(5)

machine-learning 1190

scikit-learn 640

pandas 542

keras 510

tensorflow 352

Name: tags, dtype: int64

which will trigger tasks as far back as needed up its dependency chain to return an in-memory or on-disk object, as desired.

Realistically, once a dataset can be worked with on a single machine, it will generally be much faster to do so rather than keeping it in a distributed environment.

Fortunately, Dask objects can seamlessly transfer into analogous local Python objects (for example, a pandas.Series here) when computed.

In addition to the analytics capabilities in baseline Dask, we can access a lot of machine learning functionality in the associated dask-ml package.

Let’s try to distinguish posts about Python versus R from our dataset:

>>> posts.tags = posts.tags.map(lambda tags: list(set(tags).intersection({"python", "r"})))

>>> posts = posts[posts.tags.map(lambda tags: len(tags) == 1)] # exactly one tag, not both

>>> posts.tags = posts.tags.map(lambda tags: tags[0]).astype("category")

So we’ve reduced our dataset down to posts only tagged with python or r (but not both), and discarded other tags.

The dask-ml package presents distributed equivalents to a number of scikit-learn pipeline tools:

>>> from dask_ml.model_selection import train_test_split

>>> from dask_ml.preprocessing import LabelEncoder

>>> from dask_ml.feature_extraction.text import HashingVectorizer

>>> train, test = train_test_split(posts, test_size=0.25, random_state=42)

>>> label_encoder = LabelEncoder().fit(train["tags"])

>>> vectorizer = HashingVectorizer(stop_words="english").fit(train["body"])

These will distribute their actions across the Dask cluster (although note that train_test_split will shuffle data between partitions, which can be a potentially expensive step), with the preprocessing steps returning Dask arrays suitable for machine learning algorithms.

The LabelEncoder here can benefit from the category datatype we set above for our labels, letting the cluster avoid a potentially-expensive repeat scan across the entire dataset to learn the available labels.

Similarly, the HashingVectorizer is designed to work efficiently on the distributed dataset.

Unlike something like a CountVectorizer or TfidfVectorizer in scikit-learn, which would need to collate information between partitions, the HashingVectorizer is stateless and can run in parallel across the whole dataset (since it only depends on the hash of each input token) to efficiently generate a sparse matrix representation of our text.

Once we have our data ready, Dask also gives us a number of options for scaling out ML algorithms.

For example, we can use it to parallelize grid search and hyperparameter optimization across smaller datasets, handle parallelizable tasks within algorithms like XGBoost, or manage batch learning across a partitioned dataset.

Let’s try the last option, and train a simple classifier on our data – since Dask integrates with the typical Python data stack, we can work out of the box with scikit-learn tools, only needing the algorithm to support the partial_fit batch training paradigm to play well.

>>> from dask_ml.wrappers import Incremental

>>> from sklearn.linear_model import SGDClassifier

>>> model = Incremental(SGDClassifier(penalty="l1"), scoring="accuracy", assume_equal_chunks=True)

Here we wrap our simple linear classifier (with a strong L1 norm, such that it should learn to focus on the most informative tokens in our sparse representation) in the Incremental wrapper, which will let us train on our data per-partition.

To train, we simply run

>>> X = vectorizer.transform(train["body"])

>>> y = label_encoder.transform(train["tags"])

>>> model.fit(X, y, classes=[0, 1])

Incremental(estimator=SGDClassifier(penalty='l1'), scoring='accuracy')

which looks a lot like scikit-learn with a few additional quirks – for example, the model needs to know all available classes in case one is not represented in a given batch, and the Incremental wrapper needs our assurance that chunks from X and y will be of equal size (which we can safely assume for the output of our transformer steps).

Likewise for scoring:

>>> X_test = vectorizer.transform(test["body"])

>>> y_test = label_encoder.transform(test["tags"])

>>> print(f"{model.score(X_test, y_test):.3f}")

0.896

Not too bad given we didn’t tune this at all!

moving to a remote cluster

Everything we’ve done so far works fine on our local machine, using the LocalCluster variant of the Dask cluster.

One of the ways Dask really shines, though, is the ease of transitioning this code to run on a remote cluster.

Back at the start of our pipeline, we declared a dask.distributed.Client() without any arguments.

This automatically starts up a local version of the cluster for computation.

(We could also explicitly create a dask.distributed.LocalCluster if, say, we wanted to limit its resources.)

To use a remote cluster, we simply create the client like

>>> client = dask.distributed.Client("tcp://<address:port of dask cluster>")

with the address of the remote cluster’s scheduler, then the rest of our work will largely “just work”!

Dask even gives us a handy monitoring dashboard for the cluster so we can see task progress, resource usage, etc.

(We can actually see this with our local cluster as well, on localhost:8787.)

Since we no longer can have the Dask workers referencing files on our local machine, we do need a way to get our data to and from the cluster.

Fortunately, the Dask developers also support several handy tools for interacting with cloud data stores like S3 and GCS.

For example, for data in S3 we can use the s3fs package, which gives us a filesystem-like object to work with data in S3.

In Dask, we can just directly pass an S3 path to our file I/O as though it were local, like

>>> posts = dask.bag.read_text("s3://<S3 bucket path to data>")

and s3fs will take care of things under the hood.

We can also access those files on our local machine like

>>> fs = s3fs.S3FileSystem()

>>> with fs.open("s3://<S3 bucket path>", "rb") as rf:

... data = rf.read() # or whatever file operation we want!

The last thing we need to think about for remote computing (in general, not just with Dask) is environment control. With our local cluster, the workers are executing in the same Python environment, so any packages and functions available in our own environment are available to the workers. With remote clusters, the workers are naturally running their own isolated Python environments, so we need to think about what code we have available for the workers.

Function calls that we fire off to the Dask cluster are serialized with cloudpickle, but more complex local code or references to other packages can be difficult.

Generally I try to use dask builtins as much as possible (especially in dataframes), and reference packages otherwise – since Dask is running a standard Python environment, installing packages on the workers is straightforward, and the Kubernetes resources managing our Dask cluster makes pushing those installs to the whole cluster easy.

what about Spark?

As a distributed computing and data processing system, Dask invites a natural comparison to Spark.

For my own part, having used both Spark and Dask, I’ve found it much simpler to get started working with Dask coming from a data science background.

The fact that it very intentionally mirrors common data science tools like numpy and pandas makes the barrier to entry much lower for a Python user, both for learning the tool and for scaling out existing projects.

Moreover, since Dask is a native Python tool, setup and debugging are much simpler: Dask and its associated tools can simply be installed in a normal Python environment with pip or conda, and debugging is as straightforward as reading a normal Python stacktrace or REPL output.

Compared to the nontrivial tasks of setting up local Spark for development and decyphering JVM outputs interlaced in Python code (since, realistically, a data scientist or machine learning engineer will be interacting with the cluster via pyspark), this greatly streamlines the development process.

While pyspark can integrate custom Python code, deploying it to the cluster is nontrivial (as opposed to simply pip/conda installing extra packages on the cluster for Dask, which is straightforward even in deployed clusters on infrastructure like Kubernetes).

Spark was designed specifically for conventional data processing tasks, and I’ve found its ML tooling to be rather wanting for my work compared to Dask. With that said, there are a few considerations where Dask isn’t the best option – for example, Dask currently does not have a good way to work with streaming data, whereas Spark can integrate with the spark-streaming paradigm, or talk more easily to newer tools like Apache Beam. Similarly, while Dask’s Python-native implementation can be a boon for DS/ML practitioners, it does mean it lacks the cross-language support of Spark. In short, for data engineering teams that need to integrate with other Scala/Java tools in the Hadoop ecosystem (especially streaming tools), Spark may be a better choice – but for Python-centric teams with heavy data analysis and machine learning needs, Dask can be a really powerful tool.

wrapping up

For a data scientist or machine learning engineer, migrating from single-machine code in the traditional Python data stack (numpy, pandas, scikit-learn, etc.) to a distributed computing environment can be daunting.

The Dask toolset makes that migration cleaner, with distributed analogues to much of the common Python data stack.

This enables cluster-scale powerups for your workflow – or just easy management of parallelism and disk caching on a single machine.